The decision in 1945 to employ atomic bombs against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki occurred at the end of a global conflict that had exhausted nations, devastated populations, and accelerated scientific capabilities into instruments of unprecedented destructive power. The Manhattan Project had mobilized vast resources and top scientific talent to develop nuclear weapons as a wartime imperative after discoveries in nuclear fission suggested the possibility of chain-reacting devices, and the first full-scale test at Trinity in July 1945 demonstrated the viability of an atomic bomb and removed technical uncertainty from strategic calculations.

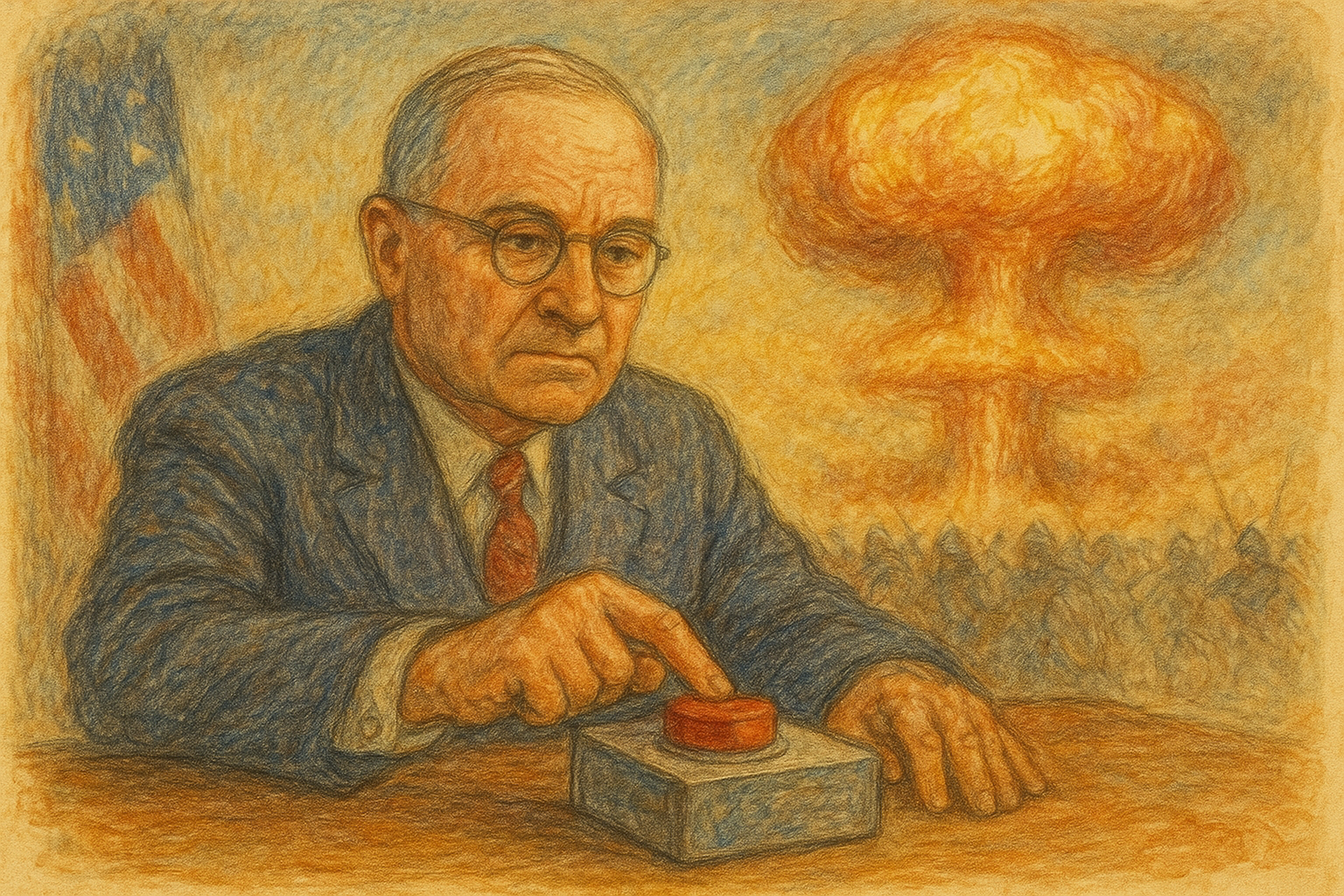

By August 1945 the Pacific war remained fierce despite the collapse of Nazi Germany in May, Japanese forces continued to resist across a wide theater, and Allied planners faced the prospect of a costly invasion of the Japanese home islands that senior military leaders estimated could produce extremely high Allied casualties. The Potsdam Declaration of late July demanded Japan's unconditional surrender and warned of "prompt and utter destruction" if it refused; Japan did not immediately accept the ultimatum and the United States authorized the use of atomic weapons against selected urban-industrial targets in the home islands. The first bomb, "Little Boy," was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6 and devastated a major city and military logistics node, and the second, "Fat Man," detonated over Nagasaki on August 9, producing massive instantaneous casualties and further direct destruction of infrastructure and life.

The human toll from the two bombings was appalling and compounded over subsequent months and years by the effects of radiation and the collapse of public health systems. Contemporary and later assessments place the number killed by the blasts and by radiation-related illnesses in 1945 alone in the range of roughly 150,000 to over 200,000 people, with estimates varying by source and methodology; many of the dead were civilians and many survivors, known as hibakusha, suffered cancers, chronic illnesses, and social stigma for decades afterward. The physical wounds of burns and blast trauma were accompanied by long-term physiological damage from ionizing radiation, a pattern that reshaped medical understanding of radiation sickness and its late effects and prompted sustained study of long-term cancer incidence among exposed populations.

The military and diplomatic rationale for the bombings has been intensely debated by historians, policymakers, and veterans since 1945. Proponents argued that the atomic strikes ended the war quickly, prevented an invasion that would have caused vastly greater casualties on both sides, and demonstrated U.S. strategic dominance that constrained postwar Soviet ambitions; critics contend that Japan was already on the brink of collapse, that alternatives such as a demonstration detonation or conditioned surrender terms might have avoided mass civilian deaths, and that the rapid second strike foreclosed meaningful Japanese deliberation over surrender. The context of emerging U.S.-Soviet rivalry and the desire to shape the postwar order in Asia also informed decisions about targeting and timing, as policymakers recognized the political implications of being the first to use—and to possess—this new category of weaponry.

The bombings inaugurated the nuclear age and transformed international relations, strategy, and moral discourse. The existence of atomic weapons produced an era of deterrence, arms races, and doctrines premised on the catastrophic logic of mutual destruction, and it prompted early and continuing efforts to regulate or limit nuclear proliferation through diplomatic instruments and treaties. The psychological and cultural imprint of Hiroshima and Nagasaki catalyzed peace movements, survivor advocacy, and a sustained global ethical debate over the legitimacy of weapons that can annihilate cities and civilian populations in moments.

The legacy of August 1945 therefore combines immediate tactical and human consequences with long-term structural change: the abrupt end of active hostilities between Japan and the Allies; a reconfiguration of power relations in East Asia during occupation and reconstruction; the medical and scientific lessons of acute and chronic radiation effects; and a reorientation of global security policy around nuclear deterrence and arms control that continues to define interstate politics and moral reckoning over weapons of mass destruction. The bombings remain a subject of contested memory, moral inquiry, and legal debate, and their consequences endure in the health of survivors, the architecture of international security, and the continuing struggle to reconcile technological possibility with humanitarian constraints.