Origins and Environment

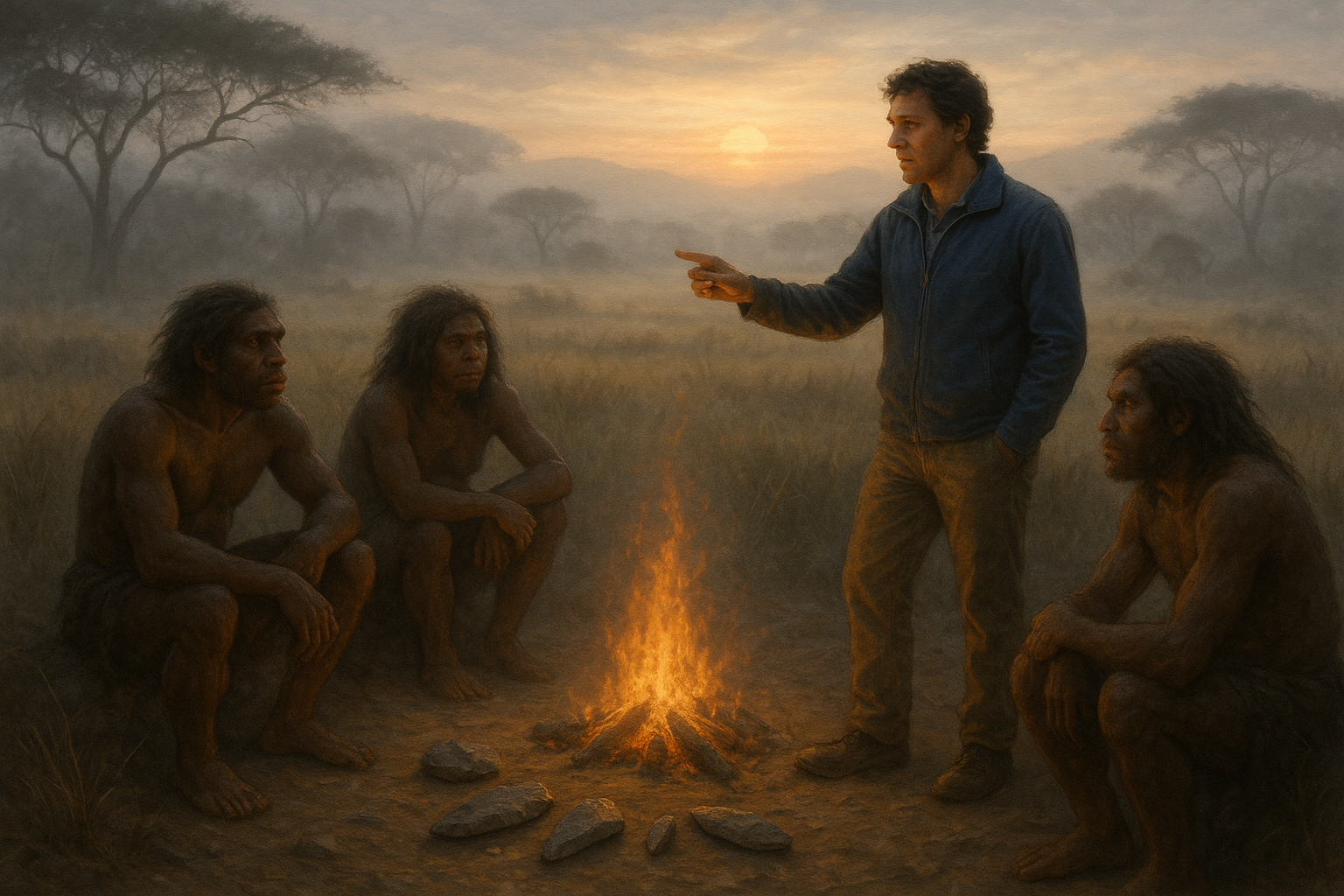

Around 200,000 years ago anatomically modern Homo sapiens first appear in the African fossil record, emerging within a Pleistocene world of shifting climates, variable ecosystems, and competing hominin species. Early humans developed a suite of biological and behavioral traits—larger brains, more gracile skeletons, sophisticated stone tool use, controlled use of fire, and increasingly complex social bonds—that together enhanced their ability to survive predators, cope with climatic stress, and exploit diverse ecological niches across Africa. These adaptive foundations allowed small, mobile bands to persist through glacial cycles and intermittent resource scarcity, creating conditions in which cumulative cultural learning and social cooperation could intensify over millennia.

Technology, Symbolism, and Social Structure

By the Late Stone Age, Homo sapiens produced more refined tools, specialized hunting implements, tailored clothing, and signs of symbolic thought such as personal ornaments and pigments, signaling growing cognitive complexity and long-range planning. Small-group cooperation underpinned subsistence strategies and childcare, while ritual, art, and burial practices began to encode social identities and shared meanings that strengthened group cohesion and facilitated intergroup exchange. Those behavioral innovations—material technology coupled with symbolic culture—became the primary toolkit that let humans buffer environmental risk, transmit knowledge socially, and expand into new regions beyond Africa.

Out-of-Africa Dispersal and Demographic Expansion

A major demographic and geographic turning point followed tens of thousands of years after the species' origin: groups of Homo sapiens dispersed out of Africa, moving along coastal and inland routes into Eurasia, Australasia, and eventually the Americas in multiple waves that reshaped global population distributions and genetic landscapes. These migrations were driven by a mix of factors including climatic amelioration, resource pressure, population growth, and exploratory behavior; they produced sustained contact, intermittent interbreeding, and competition with other hominins such as Neanderthals and Denisovans, leaving genetic traces visible in modern human genomes. The spread of humans into varied habitats stimulated technological and cultural diversification adapted to deserts, steppes, forests, and maritime environments, creating the deep substrate of regional differences that later histories would inherit.

Ecological Impact and the Long Arc Toward Civilization

The prolonged human presence across continents gradually altered ecosystems through hunting, the management and translocation of plants and animals, and the use of fire—processes that, in aggregate and over millennia, contributed to faunal extinctions in some regions and to new ecological configurations that human communities exploited and shaped. These long-term ecological engagements set the stage for later transitions: sedentism, intensified resource management, and the independent origins of agriculture in multiple world regions after the terminal Pleistocene. Those transitions from mobile foraging to settled food production provided the demographic surplus, labor specialization, and social complexity necessary for the rise of villages, cities, and states millennia later.

Cultural Foundations and Human Plasticity

The most consequential legacy of early Homo sapiens lies in their combination of biological capacities and cultural plasticity: the ability to innovate materially, learn socially, form extended kin networks, and create symbolic systems that organized social life and memory. That flexibility explains how small bands of hunter-gatherers could, over deep time, generate linguistic diversity, artistic traditions, technological repertoires, and complex social institutions that would be elaborated into languages, mythic frameworks, and political orders across the globe. Early patterns of mobility, exchange, and adaptation therefore underwrote human resilience and created the conditions for cumulative cultural evolution that accelerated after the end of the last Ice Age.

Significance for World History

Situating the emergence of Homo sapiens at roughly 200,000 BCE highlights a foundational chapter of world history: the slow accretion of traits and behaviors that enabled humans not merely to survive but to transform environments and invent cultural worlds. The species' initial ecological strategies and migratory dispersals laid the demographic, genetic, and cultural groundwork from which all later civilizations, technologies, and global interactions arose. Understanding this deep prehistory clarifies why human societies diverged across regions, how early adaptations produced enduring capacities for innovation and cooperation, and why the arc from Paleolithic bands to complex states is part of a single, expansive human story that begins in Africa and radiates outward across the planet.